Tools for Conceptual Designers

Too many, or too few?

The thought process of conceptual design is quite different from that of design documentation. Conceptual design explores possible alternatives making a series of decisions which lead us someplace new, while design documentation sets those decisions in stone crystalizing the chosen alternative into a legal contract guiding construction. Both involve drawings, but are on opposite ends of the flexibility/precision spectrum.

Conceptual design requires an open mind to explore possibilities. Do your tools disappear and let you focus only on the design?

It makes sense that a single method or a single software tool is unlikely to be optimal for both tasks. I'm certain you have wrestled with the question of the best tool for the job and have a pattern that works for you and your office. Let's face it, all computer tools are enormously complex. They can impede the design process rather than enabling it. Learning to use any one package with proficiency takes a substantial investment of time and energy. The investment in learning time far outweighs the dollar cost of software.

In my experience using any software package can be a delight or torture depending on 2 things. The first is the fit of the tool to the task at hand. The second is one's familiarity and practice with the toolset. Stumbling about in more than one half learned software package, each with a different user interface, is a nightmare scenario to avoid. If you are tasked with both conceptual design as well as design documentation, a single software tool is probably too few. Juggling too many is probably unrealistic as well. When I was a young professional I expected computer software by now to mature to the point where even the most powerful software would be as easy to use as markers, but it's not. Markers and onion skin may stick around forever. The key idea is to be so familiar with your tools that they disappear while you are designing.

Conceptual Design Toolset

If the task at hand is conceptual site design, then the toolset needs certain abilities to fit that task. We will ignore design documentation for the moment.

Basic

Layers with transparency for a clear view of the 'base'

Strokes of various widths

Filled areas

Scale

Geometric constraints

Basic sketching on inexpensive tracing paper enables all these attributes using pencil, pen or marker along with a scale and template as extras.

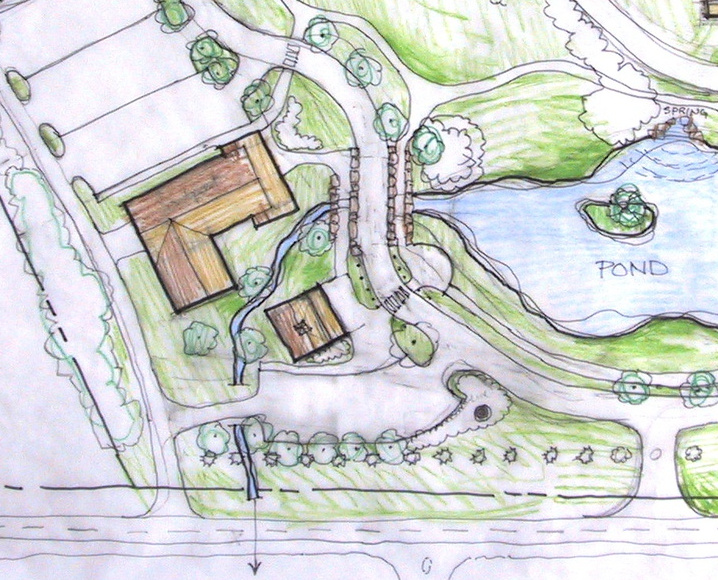

Hand drawn colored pencil sketch plan

Attractive designs and attractive renderings can result, but a more robust toolset can leverage and amplify your efforts. Leverage and power come from refined reuse. Computer tools make some nice effects easy.

Digital Step 1

Text

Symbols (stamps, blocks, components)

Line and fill styles

Images

All of us old-timers remember using press on lettering, chartpack tape, and symbols photocopied onto clear adhesive sheets as the analog to modern computer tools. Historically speaking, in the 1990's CAD software was just starting to gain traction, but it was Photoshop 2.5 in 1992 that enabled us to do things that were very hard to do before. We could create a rendering of a scene that looked like a photograph through photo editing.

At that time, CAD software was pretty dull looking with lots of graphical limitations. The only attractive renderings were by hand or with Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator. The modern versions, including their open source equivalents Gimp and Inkscape are more refined and capable but have remained the foundation of 2 dimensional graphics.

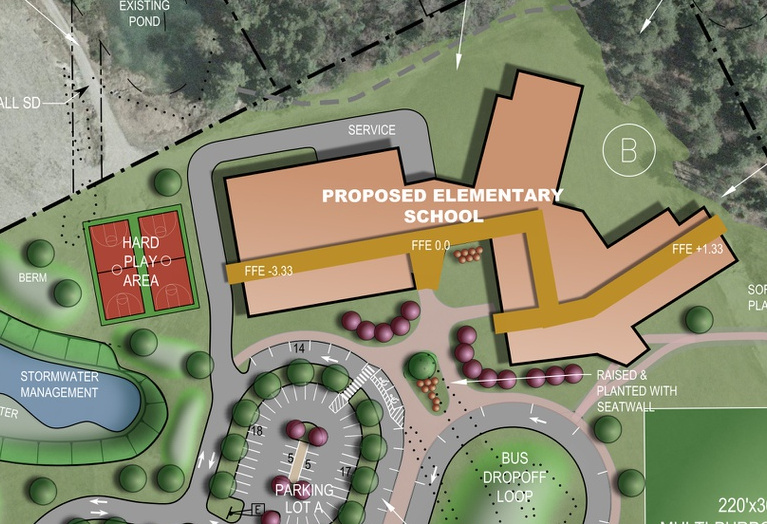

Mouse drawn vector software sketch plan

These 4 programs, Photoshop / Gimp for raster graphics, and Illustrator / Inkscape for vector graphics, also fit the task of conceptual design as they intentionally mimic pencil, pen and marker tools with added leverage of symbols, line and fill styles and images. I group these raster and vector programs together as there is crossover in their tool-sets with each having some capacity for the other. They also share a lot of user interface elements making it reasonable to be proficient in both.

Digital Step 2

3D

Lighting/Environment

Presentation - multiple viewpoints

Since our experience is in 3 dimensions, we design with 3 dimensions in mind. Designers who sketch out conceptual design with marker often draw a plan view and an elevation siew side by side while considering scale and proportion. Computer tools leverage 3D thinking first by unifying the plan and elevation drawing effort, and second by making viewpoint switching fluid and potentially effortless.

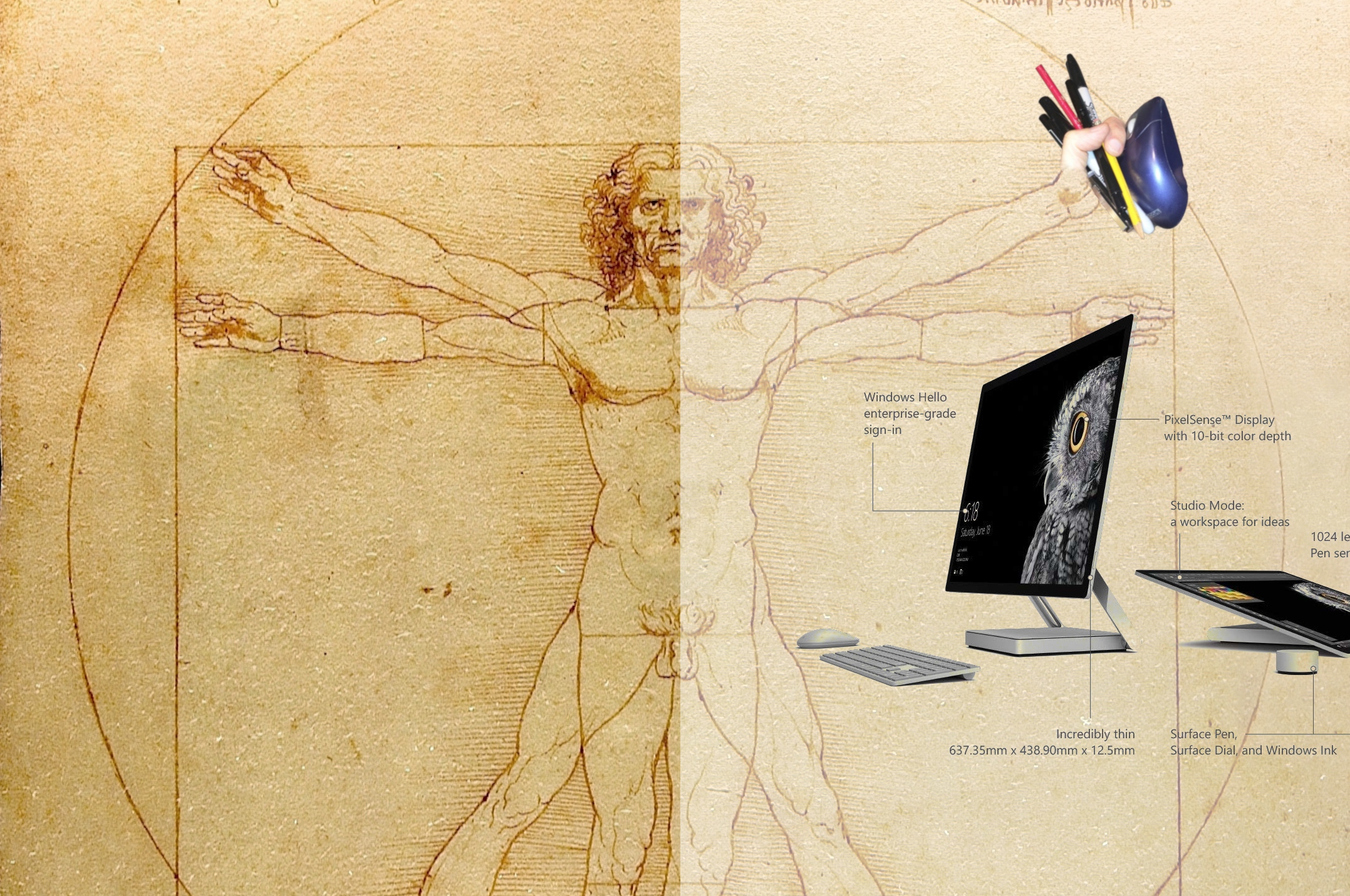

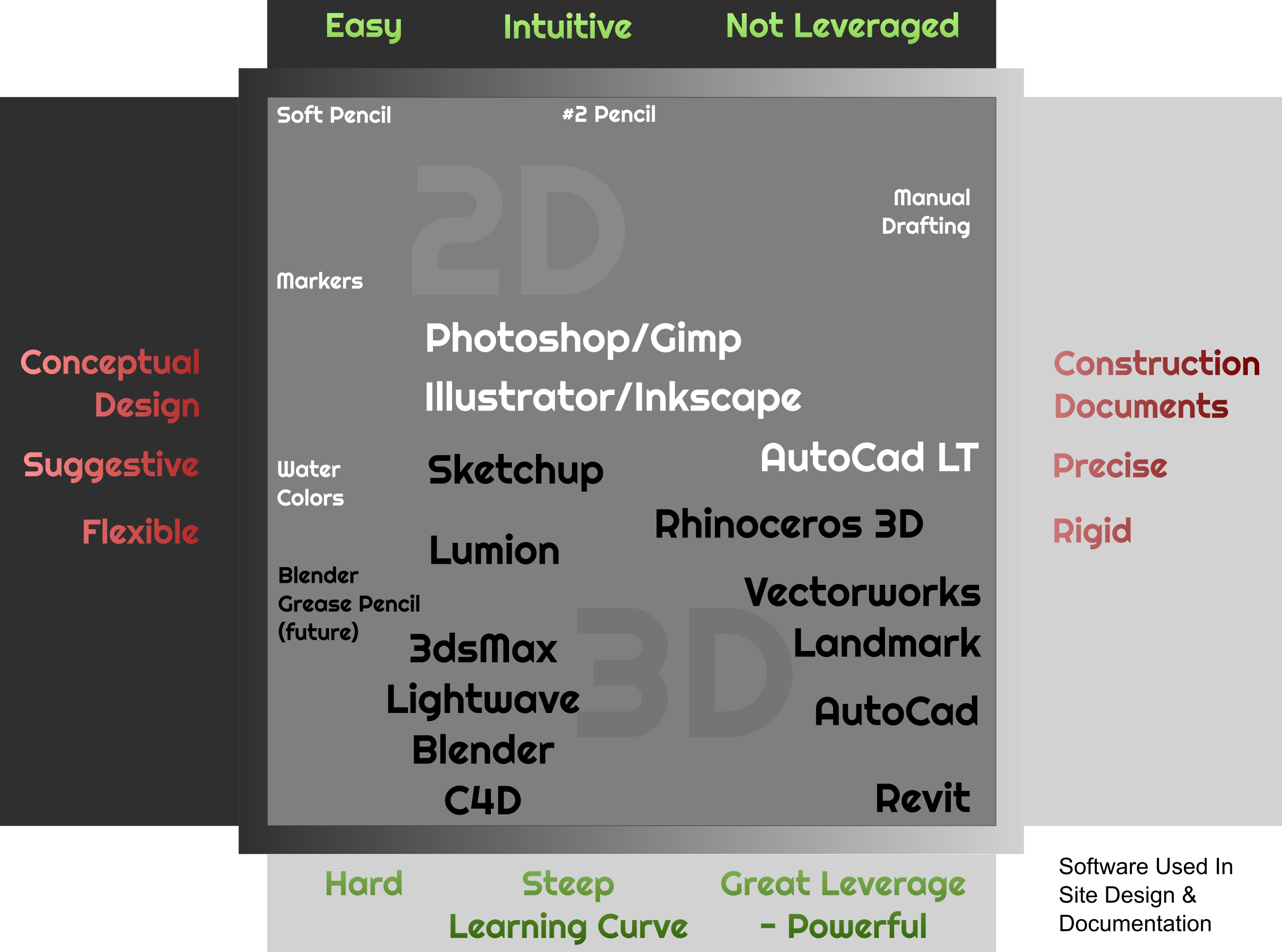

The following diagram lists drawing/modeling/rendering tools that vary from flexible and suggestive on the left to precise and rigid on the right. The drawing tools vary from easy and intuitive near the top to difficult with a steep learning curve near the bottom. This is just my opinion and are only relative to each other rather than any specific measure. The 2D tools are in white text with the 3D tools in black text.

software diagram

The most intuitive 3D program in the diagram is Sketchup. It maintains the idea of using a pencil to draw out shapes, and does a marvelous job of snapping to axis and key points like corners and center points without issuing specific commands making some 3d modeling tasks effortless. There is still a learning curve for more advanced features, and it not well suited to freeform curves. It is often used as part of a conceptual design process.

Rhinoceros 3D is not focused on simplicity, but it is well suited to freeform curves as well as general 3d modeling. It is highly precise, but the user interface is more intuitive than Autocad 3D. It is still a stretch for conceptual design unless you are very familiar with it.

Both Sketchup and Rhinoceros 3D are modelers and include only basic shadows and rendering characteristics. To prepare presentation renderings in a realistic style additional software is needed. Lumion fills the gap by importing your models and providing an enormous library of entourage including plants, people, and cars. It's game engine techniques allow fully rendered environments like beach, desert or mountain and the ability to move through your scene in real time. You arrange your model(s) created in an outside program along with the plants and other elements into a scene from which you produce snapshots and moving videos. Lumion does not stand alone but teams well with modelers like Sketchup, Rhino, Revit, Archicad or Vectorworks. It's subscription pricing is expensive, but it's ease of use makes it a good fit for conceptual design.

Vectorworks Landmark is designed to be a complete end to end software package for site design by Landscape Architects. There is no question it covers the construction document end with power, leverage and a touch of grace and ease of use, but although I have not used it, the feature list does not seem to have freeform sketching tools. I don't think you start there until you have a pretty good idea of the shape and basic geometry your design is going to take. Like Autocad, it's roots are precision drafting. Revit falls in the same camp of a highly leveraged precision modeler intending to make construction documentation effortless.

The group of 3D modeling packages designed for the entertainment industry include 3dsMax, Lightwave, Blender and Cinema 4D. These are multi-purpose modeling/rendering software that include at least one render engine for producing polished images and animation. These each are very complex with the capability of producing any graphic you can imagine. They are often used for architectural illustrations of completed designs. The odd thing is that some of their characteristics give them a fit to conceptual design as well. The first characteristic is their extreme flexibility. They contain many tools for organic freeform shaping. The second characteristic is a range of rendered output available from suggestive to realistic. Their main downside is the steep learning curve.

Blender deserves special mention because of it's rapid transition from unnoticed oddity to serious contender. It is an open source project funded and developed by many volunteers and contributors and is completely free to download and use. It still has a steep learning curve but with the emergence of the most recent version 2.80 (at the time of this writing) it is a bit easier than it used to be. It also includes a feature unique to Blender called Grease Pencil designed for 2D animation but functions in 3D as well. It operates like writing on your computer screen with a grease pencil, but the marks stick to 3D space and are edited like 2D paint programs. Keep an eye on that for the future. I think it may become a useful tool for conceptual design, particularly with a general purpose modeling and rendering toolset waiting in the wings.

Lightwave also gets special mention as I chose it for my own illustration work years ago based on the high visual quality of it's built in render engine. It works for conceptual design as well as modeling and rendering for me because of familiarity after years of use. The following images show a pocket park designed and illustrated with Lightwave.

Recommendations

If you exclusively use markers on onion skin, I recommend you explore the leverage that can be gained by learning a software tool. If you only use 2D in conceptual design, I recommend you explore a 3D option. However, if you use everything listed, you might want to dial it back a little and focus on proficiency over depth. Conceptual design requires an open mind to explore possibilities. You know you have arrived when the tools disappear and the focus is only on the design.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus